Taylor Aucoin

The Deposition Dramas blog series highlights some of the rich human stories preserved in early modern court depositions, the primary source material for the Forms of Labour Project. Each post in the series follows a different court case, diving into the narrative of these legal documents to explore the comedies and tragedies of everyday life and work in early modern England.

About a month before Christmas 1626, a company of men approached the house of one ‘Duck-wife Lucas’ in Hoghton, Lancashire, knocking at her door and demanding ‘to come in and drink’. Being ‘about ten of the clock in the night time’, the whole family were then in their beds. Nevertheless, Henry Lucas, the duck-wife’s son, arose to let the company in and fill them some ale. After a time, members of the party, particularly two named James Garstang and Edward Cattrell, grew ‘outrageous and unruly’, and demanded Henry ‘give them some pudding’. Henry answered that ‘he could give them none’, and then fetched his mother out of bed.

Duck-wife Lucas quickly moved to placate the rowdy group, assuring them they ‘should have anything in the house that was fitting’, as long as they would ‘keep good order among themselves’. This proved too much to ask. No sooner had she taken ‘water & set over the fire & boyled two puddings’, then someone filched them ‘out of the pan…before they were half-ready’. Then the company began taking down cheeses ‘from the shelf’, cutting, eating, and absconding with them ‘at their pleasure’. But Garstang and Cattrell soon went beyond discourteous cheese-eating and pudding-pinching. Evidently feeling affronted in some way, they gave ‘fowle words’ to Henry Lucas and his mother, before finally levelling this ominous threat: ‘they would be even’ with Duck-wife Lucas, ‘before hunting time went out’.

Such was the information Henry Lucas gave to a justice of the peace on the last day of May 1627. His testimony, along with those of five other men, provided evidence for a criminal case that had been the talk of the township for half a year, and would now be heard at the Midsummer Quarter Session in Preston. For as Henry concluded in his deposition, a few nights after her threatening treatment Duck-wife Lucas had ‘a black heifer [young cow] stolen out of her ground’.[1]

[1] Lancashire Archives, QSB/1/25/31.

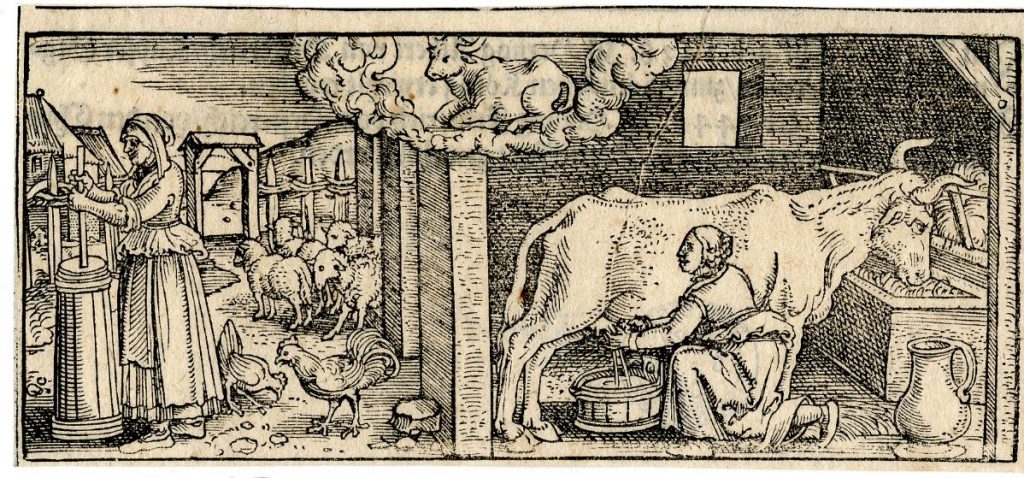

Illustration of April in Michael Beuther, ‘Calendarium Historicum’ (Frankfurt, 1557) ©The Trustees of the British Museum CC BY-NC-SA 4.0