James Fisher

This is the second post in a short series on different strands of research into pauper apprenticeships as a compulsory form of labour. Read Part I here.

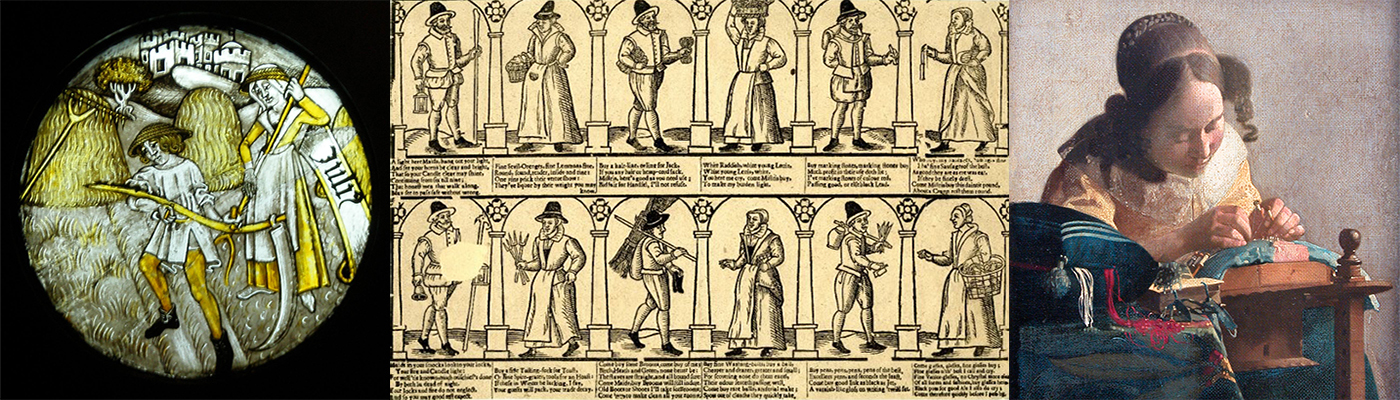

The essence of an apprenticeship is the exchange of labour for training. Hence when examining pauper apprenticeships, we immediately have to confront the basic question: Were they seriously intended to provide training for poor children, and if so, to what extent was this achieved in practice?

After over a century of scholarship there is still no clear consensus. Broadly speaking, a negative view has prevailed that training was not the primary policy aim of pauper apprenticeships or a key contractual duty of the master. Instead, the aim was simply for the child to be maintained and to relieve the burden on their parents and the poor rate.[1] But this account has been repeatedly challenged by those who paint a more nuanced or even positive picture.[2] In particular, many have insisted that there was at least a minimal intention for children to learn something of practical use to enable them to support themselves in adulthood.[3]

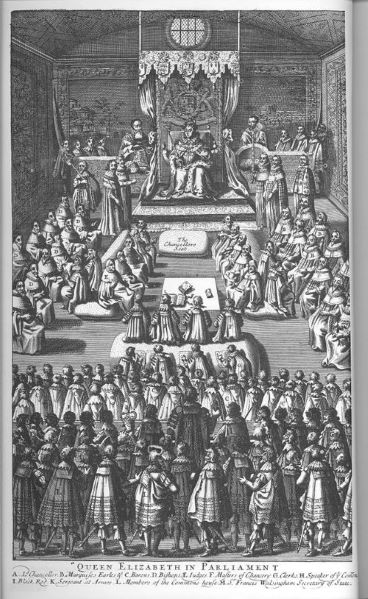

One way we can examine the intentions of authorities is to focus on the apprenticeship contracts (indentures) that defined the legal arrangement and specified the duties of the master. Continue reading