Taylor Aucoin

The Deposition Dramas blog series highlights some of the rich human stories preserved in early modern court depositions, the primary source material for the Forms of Labour Project. Each post in the series follows a different court case, diving into the narrative of these legal documents to explore the comedies and tragedies of everyday life and work in early modern England.

About a month before Christmas 1626, a company of men approached the house of one ‘Duck-wife Lucas’ in Hoghton, Lancashire, knocking at her door and demanding ‘to come in and drink’. Being ‘about ten of the clock in the night time’, the whole family were then in their beds. Nevertheless, Henry Lucas, the duck-wife’s son, arose to let the company in and fill them some ale. After a time, members of the party, particularly two named James Garstang and Edward Cattrell, grew ‘outrageous and unruly’, and demanded Henry ‘give them some pudding’. Henry answered that ‘he could give them none’, and then fetched his mother out of bed.

Duck-wife Lucas quickly moved to placate the rowdy group, assuring them they ‘should have anything in the house that was fitting’, as long as they would ‘keep good order among themselves’. This proved too much to ask. No sooner had she taken ‘water & set over the fire & boyled two puddings’, then someone filched them ‘out of the pan…before they were half-ready’. Then the company began taking down cheeses ‘from the shelf’, cutting, eating, and absconding with them ‘at their pleasure’. But Garstang and Cattrell soon went beyond discourteous cheese-eating and pudding-pinching. Evidently feeling affronted in some way, they gave ‘fowle words’ to Henry Lucas and his mother, before finally levelling this ominous threat: ‘they would be even’ with Duck-wife Lucas, ‘before hunting time went out’.

Such was the information Henry Lucas gave to a justice of the peace on the last day of May 1627. His testimony, along with those of five other men, provided evidence for a criminal case that had been the talk of the township for half a year, and would now be heard at the Midsummer Quarter Session in Preston. For as Henry concluded in his deposition, a few nights after her threatening treatment Duck-wife Lucas had ‘a black heifer [young cow] stolen out of her ground’.[1]

[1] Lancashire Archives, QSB/1/25/31.

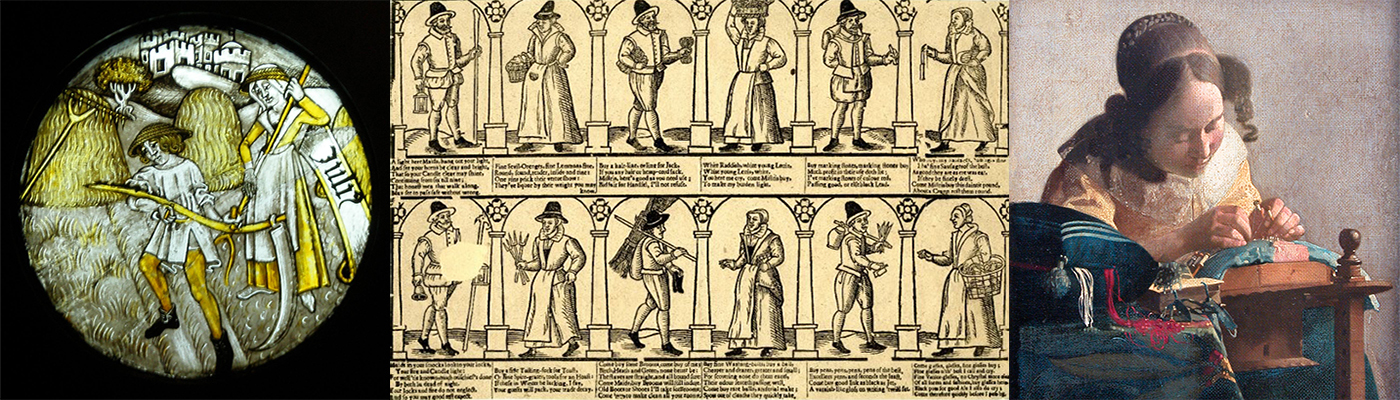

Illustration of April in Michael Beuther, ‘Calendarium Historicum’ (Frankfurt, 1557) ©The Trustees of the British Museum CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Aside from the intrigue of the hijacked heifer, Henry’s one-page deposition contains much of interest to the social historian. There’s information about time-use (what hour the family was abed) and time-reckoning (the reference to ‘hunting time’). There are signs of atypical household structure in the descriptions and interactions of Henry Lucas (a husbandman) and his mother (a duck-wife). ‘Husbandman’ would normally imply Henry headed his own household and farm, yet he seems to have lived in the house and under the authority of his mother. Unlike most women in early modern court records, she was described by her occupation (someone who keeps ducks), rather than her marriage status (spinster, wife, widow). Beyond duck-keeping, it’s heavily implied she was an alehouse keeper (though that’s never stated outright), and she certainly owned some cattle. Clearly, Duck-wife Lucas was a woman of some economic position and power.

The distinct work activities listed in Henry’s blow-by-blow account speak to these questions about gender, labour and authority (our project’s primary interests). Why, for example, did Henry decline to provide puddings after otherwise catering to these guests? Did he lack the necessary cooking skills? Was this a task thought unfit for a husbandman? Was it outside his authority to portion out his mother’s goods? Or was he simply fed up dealing with these annoying drunks alone? Whatever the case, Henry went into obsessive detail about his mother’s cookery, recounting each step of her work and lingering over the great scandal of the purloined puddings, snatched from the pan before their time, ‘but by whom [he] kneweth not’. To Henry this seemingly small matter was no mere trifle!

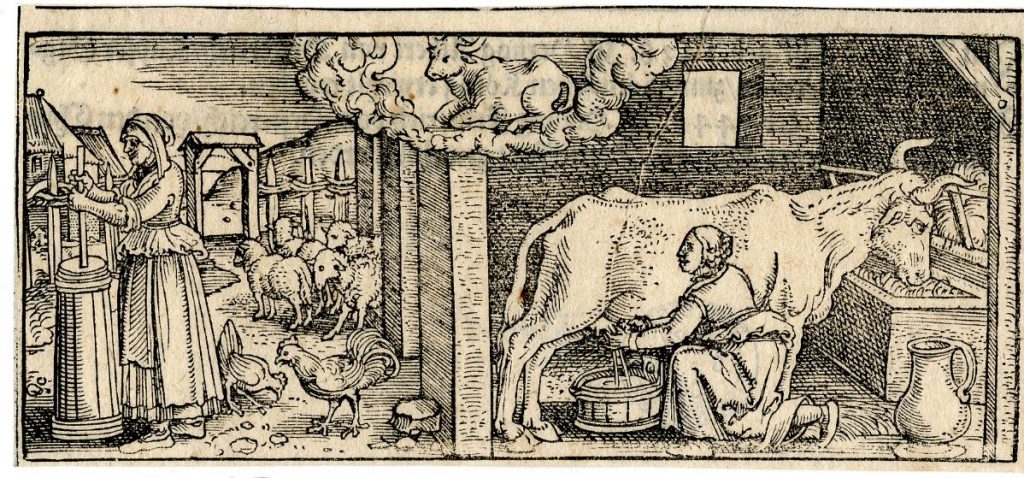

Diego Velázquez, Old Woman Frying Eggs, c. 1618, National Gallery of Scotland. Public Domain.

What’s less clear is how such ostensibly irrelevant minutia pertained to the case of the stolen cow. Perhaps Henry was trying to establish the context of the threat against his family, and the ill-fame of those he suspected of the heifer theft. But regardless of their value as legal evidence, these little particulars provide rare insight into the experience and specifics of early modern food production, and are exactly the kinds of ‘work activities’ we collect for our project database. Work practices also suffuse the other case depositions, which pick up the story in later months.

As the carpenter William Dawson deposed, not long after the heifer went missing, ‘ the matter was spread abroad and in everybody’s mouths’. During Lent, masons, stonemen, wallers and husbandmen working at stone delfs (quarries) in nearby Wheelton and Withnell, ‘did falle in talk about the said heifer, wondering who [did] steal her’. This seventeenth-century watercooler gossip – a glimpse of intersecting labour and sociability in the local industrial economy of upland Lancashire – soon brought damning evidence against the culprits to the surface. One stoneman, William Horrobyn, ‘did of his own mere motion’ report that James Garstang, with some accomplices, had done the deed and given the heifer to Edward Cattrell. Garstang would later confront Horrobyn about the matter a few weeks before Easter, digging himself a hole even deeper than the stone delf when he angrily confessed: ‘I have done the said Lucas wife wrong & if she complayne I will do her a further injury’.

But the Lucas family would not be cowed. Nor were they content to simply wait for justice to run its course. According to Dawson, Henry Lucas travelled some 25 miles to Hebden Bridge in Yorkshire, to meet ‘with a wiseman to know which way the said heifer was gone’. The ‘wiseman or witch’ showed Henry ‘in a vision, those persons that took the said heifer’ and told him it was being kept ‘between two corn moughs [stacks]’. As several surviving recognizances (bonds to appear in court) demonstrate, the Lucas family would later move to prosecute Garstang, Cattrell and their accomplices at the quarter sessions, though it’s unclear whether the magical consultation (itself a form of work) influenced this decision.

While the evidence appears stacked against Garstang &co, the depositions (as is typical) do not provide a verdict for the Midsummer trial. Related sources like indictments, when they survive, sometimes contain such information, but even with them we are always left with but part of a story. Frustratingly, many questions remain that will never be answered. Was the wiseman’s vision accurate? Did Duck-wife Lucas ever get her heifer back? And of course, the burning question on everyone’s lips: who pinched the puddings from the pan? Whoever that villain was, we can only hope he got his just deserts.