Taylor Aucoin

On the night of 8 April 1693, a burglar broke into Thomas Masterman’s house in Stokesley, making off with the hefty sum of £2 10s. To identify the thief and reclaim his money, Masterman trekked south through the north Yorkshire moors to Byland Abbey. There he met with William Bowes, described by Masterman as ‘a man who pretends to discover stolen goods by casting of figures or otherwise’. Bowes proceeded to do just that, and ‘in a glass did show…the likeness & physiognomy of Richard Lyth’, a tailor to whom Masterman had recently repaid a small debt. Bowes advised to look no further than Lyth for the thief, adding that, ‘he could not have power to dispose of the money, but within a few days it would be brought again & thrown in a corner near [Masterman’s] house’. For this information and service, Bowes received one shilling in payment.[1]

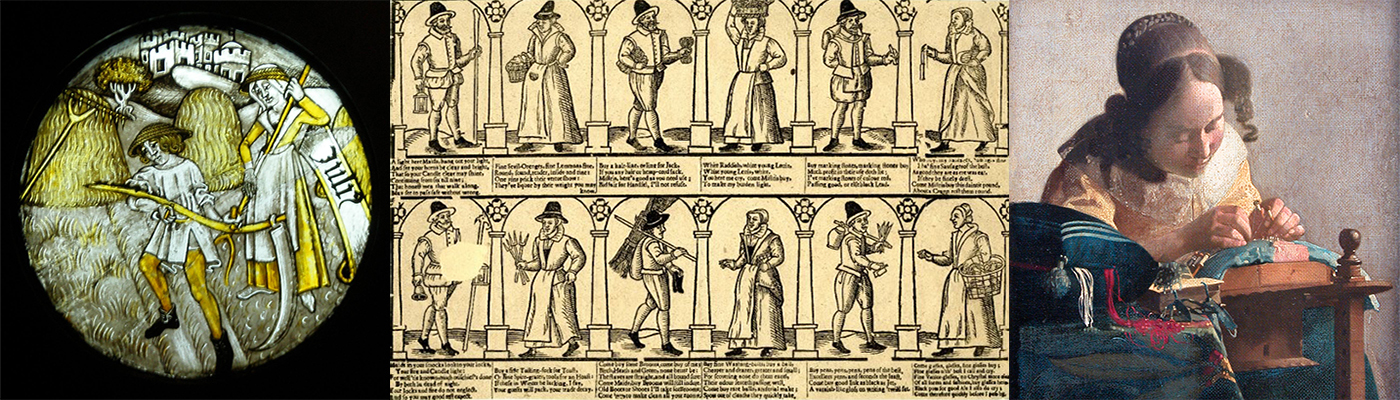

Masterman’s story, captured in a court deposition from the North Riding of Yorkshire, is not altogether unusual for the time. We know that many premodern English men and women similarly consulted and contracted local magical practitioners (variously called wisemen, cunning folk, or soothsayers) to cure ailments, find lost or stolen property, or fix other problems. While reading through court depositions from quarter sessions of the peace for counties of northern England, I’ve come across a number of references to such ‘practical magic’, as well as more classic examples of malicious witchcraft. And since it’s Hallowtide, it seems the perfect time to survey these magical findings and discuss their relevance to the project: what they suggest about the relationship between work and magic during this period, and the ways in which some magical activities could constitute ‘forms of labour’ in their own right.[2]

In the northern quarter sessions at least, I’ve found that depositional evidence of magic usually derives from just a few types of criminal cases. Continue reading