Hannah Robb

In June 1614, ‘on a day of correction’ held at the house of widow Elizabeth Thalthropp in Thirsk, Yorkshire, Thomas Bell, vicar of Felixkirk, accused the gentleman Thomas Edmondson of being a ‘huge knave’, a ‘notorious usurer’ and threatened to ‘make him do penance for his usury’. The words were spoken before a congregation of churchmen and neighbours gathered in Elizabeth’s home and led to a hotly contested suit of defamation. The depositions that followed reveal the activities of a professional money lender in the early seventeenth century.

This case really struck me when I encountered it in the deposition books from the Consistory Court at York as part of my research for the Forms of Labour project. Evidence of formal money lending in the depositions is not usually as clear as in this case. We have indications that long running accounts were ‘reckoned’ at harvest time when tithes were due and instances of testamentary cases show executors were left chasing outstanding debts owed to the deceased. Clearly the credit economy was prevalent in many of the exchanges and relationships we encounter in the deposition books. Rarely however, are there explicit accounts of the work involved in formal money lending. However, in this defamation case we have evidence that formal lending was indeed prevalent in the rural economy.

Three deponents confessed to having borrowed significant sums of money from Edmondson. William Flower had borrowed £30 in 1611. He repaid £13 in a single payment and became bound for a further £20 of which, at the time of his deposition some three years later, he still owed 40s. Thomas Kowpe borrowed £20 or £30 for six months at a rate of 2s to the pound and a sack of oats. Edmondson charged both Flower and Kowpe ten percent interest on their loans. It was claimed Edmondson ‘never took excessive fees’ so the oats may have been in lieu of such costs. Edmondson appears to have relied on written accounts to keep track of his business. He employed Robert Lupton, a public notary in Kirkby, to draw up bills and bonds for his loans. When he lent £40 to one John Pierce he allowed him to repay weekly over the course of ten years. When Pierce had repaid £36 Edmondson kept a bill of the payment and four years later used it as evidence in a suit against Pierce at court.

How common were professional money lenders in the early seventeenth century? Though contentious, money lending and the charging of interest was granted an air of officiality by the Church. We find other members of the clergy participating in the exchanges. Radolphus Betson who was curate of Bagby stood as surety when Edmondson made a loan to Thomas Kowpe, a practice derided in the writings of Luther, and it was Betson who recalled the interest that was charged. Edmondson also appears to have held an official role in the church acting as registrar for the Archdeacon of Cleveland, supporting the maintenance of records in the archdeaconry and assisting in the appointment of the Bishop. The notary Robert Lupton claims that the rates charged by Edmondson were standard across all registrars working in the Archbishopric of York. Edmondson also ‘lent good sums of money to diverse person gratis’, a practice common amongst registrars of the church, where ‘if the party was poor less was taken’. Lupton recalls that only one instance of usury had been presented before the consistory court of York in his memory and that it was dismissed when the standard rate of 2s was found to have been charged.

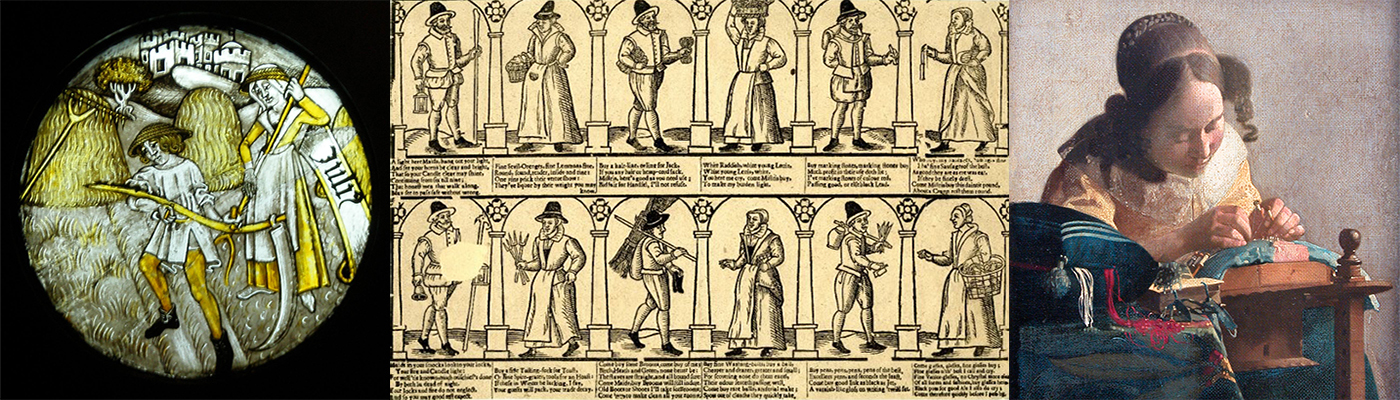

Formal money lending and the charging of interest was clearly prevalent and supported by the Church with money regularly loaned amongst church officials. The admonition of the usurious money lender remained a common trope in the literature of early modern England suggesting that, if not in practice, concerns about money lending and interest were widely felt. William Flower recalled how he had read a book against usury entitled The Speculation of Usurie authored by the same Thomas Bell who had accused Edmondson of usurious practices. Bell was against the charging of interest in all forms. In his book Bell considers the economic theory of interest and states that no interest can be charged on money for money is by its own nature ‘barraine and fruitlesse, and so can never yield any commoditie, unless it be by the industry of man’. Usurers were, he claimed, ‘unmercifull and very cruell men that they take pleasure in the miserie of the poore, and will have no compassion on them’.

In this single case we can observe the wider debate about the role of money lenders in the English economy and the morality of the market at a time when fears over a decline in charity and neighbourliness were rife; a national debate played out in the microcosm of Thirsk. What the case reveals is that Bell did not necessarily represent the views of his peers who came forward to support Edmondson and who stood as surety in his financial dealings. Nor was Edmondson a lone operator. He was one of many professional lenders operating in their official role within the church where interest was routinely charged. He employed the labour of the public notary, issued bills and managed his accounts. When we think of the credit economy of early modern England we need then to consider the role of professional lenders and the church more broadly in supporting loans despite an abundance of literature against the practice.

Further reading

York Borthwick Papers, CP.H.1171, Defamation Edmondson v. Bell, 3/10/1614-20/7/1616.

Thomas Bell, The Speculation of Usurie, (London, 1596).

Dave Postles, ‘The Financial Transactions of An Archdeacon, 1604-20’, Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society, 86 (2012), 149-163.

- Holderness, ‘The clergy as money-lenders in England, 1550–1700’, Princes and Paupers in the English Church, 1500-1800, eds. Rosemary O’Day and Felicity Heal, (Leicester, 1981), pp. 195–209.