James Fisher

The best introductions are fashionably late and retrospective, right?

I began my 3-year project researching pauper apprenticeships in the summer of 2020, which will contribute to a key strand of the FORMSofLABOUR project examining the relationship between freedom and different forms of work in early modern England. This is the first in a short series of posts to introduce the topic, share some provisional research, and explore a few puzzling features.

Here I will provide a brief sketch of the overall approach and intervention into current historiography, before illustrating this with a closer look at the statutory origins of pauper apprenticeships.

A Distinct Form of Labour

The basic approach is to investigate pauper apprenticeships as a device of labour regulation as well as poor relief. As a key provision in the consolidated Poor Law of 1601, the apprenticing of poor children by parish officers has overwhelmingly been studied as a response to and way of managing poverty. But this framework is too limited.

Firstly, its distinctiveness as a form of work – as compulsory, unpaid, long-term service in another’s household, for both girls and boys – has rarely been addressed in any depth. The working lives of pauper apprentices has mostly been considered from a humanitarian perspective concerned with the treatment of the child in terms of abuse by masters or miserable living conditions. This project seeks greater understanding of the structural condition that left children vulnerable to potential abuse, namely their lack of freedom as workers.

Secondly, the narrow focus as a provision within the Elizabethan poor law obscures its role within a wider set of laws governing labour and vagrancy. As outlined below, pauper apprenticeships arose as part of a package of measures to control the labouring poor and this context must be maintained when analysing their enforcement in different local areas.

Thirdly, following both these points, a full understanding requires a comparative analysis with other forms of work, especially compulsory service, which perhaps dovetailed with apprenticeships in the regulation of poor youth. Those studies that have compared pauper and regular apprenticeships tend to view the former as an unproblematic sub-category of the latter, without confronting its coercive dimension and function as part of wider social policy.

The rest of this post presents a critical summary of the statutory origins of pauper apprenticeships, in order to properly define the topic, clarify the period under scrutiny, and elucidate the interlocking nature of the sixteenth-century poor and labour laws.

Statutory Origins

When I attempted to clarify the development of statutory law on pauper apprentices I found considerable variation in opinion. The legislative basis established in 1598 and 1601, which would remain essentially unchanged for over two centuries, is perfectly clear.

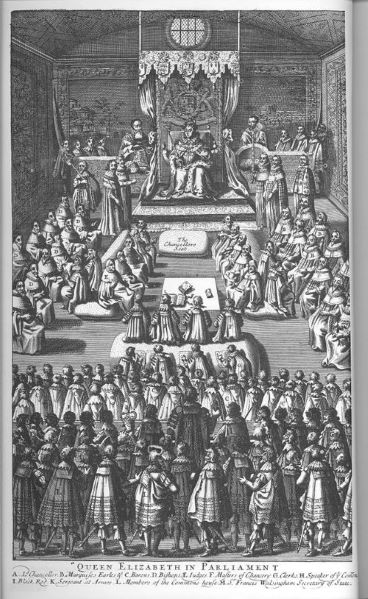

The important fourth clause in the 1598 Act for the Relief of the Poor (39 Eliz. I, c.3) gave power to churchwardens and overseers, with the consent of two Justices of the Peace, to bind any child (whose parents could not maintain them) as an apprentice until the age of 21 (girls) or 24 (boys). This was reiterated in 1601 (43 Eliz. I, c. 2) with the qualification that girls could be released upon marriage before the age of 21.[i]

However, while historians have been aware that there were earlier precedents, their surveys have been very brief with little agreement about detail. The following table presents a summary of key pre-1598 statutes, a brief description of the relevant clause, and lists the historians who have cited them.[ii]

| Statute | Relevant Clause | Identified By |

| 1536

Act for punishment of sturdy vagabonds and beggars (27 Hen. VIII, c.25) |

Children aged 5-14 in ‘begging or idleness’ can be appointed to ‘masters in husbandry’ or crafts [clause VI] | Dunlop & Denman (1912)

Rose (1989) Simonton (1991) Hindle (2004) |

| 1547

Act for the punishment of vagabonds and for the relief of the poor and impotent persons (1 Edw. VI, c.3) |

Beggars’ children (any age) & vagrant children aged 5-14 can be taken ‘servant or apprentice’ until 20 (girl) or 24 (boy); enslavement for runaways [clause III] | Dunlop & Denman (1912)*

Rose (1989) Beier (2008) McIntosh (2011) |

| 1550

Act touching the punishment of vagabonds and other idle persons (3&4 Edw. VI, c.16) |

Beggars’ children & vagrant children aged 5-14 can be taken into ‘service’ until 15 (girl) or 18 (boy), to whatever occupation [clause X] | Rose (1989)

|

| 1563

Act touching diverse artificers labourers servants of husbandry and apprentices (5 Eliz. 1, c.4) |

Youth aged 10-18 can be taken as apprentices in husbandry until age 21 or 24 (by indenture) by householders with sufficient land; those under 21 can be compelled into apprenticeship [clause XVIII & XXVIII] | Dunlop & Denman (1912)

Sharp (1991) Simonton (1991) Lane (1996) |

| 1572

Act for the punishment of vagabonds, and for the relief of the poor and impotent (14 Eliz. 1, c.5) |

Beggars’ children aged 5-14 taken into ‘service’ by anyone of ‘honest calling’, bound to 18 (girls) or 24 (boys) [clause XXIV] | Kussmaul (1981)

Rose (1989) Simonton (1991) Hindle (2004) Beier (2008) McIntosh (2011) |

*The act cited is ‘3 Edw VI. c.3’, which seems to be a confused amalgam of 1547 and 1550, but explicit mention of slavery indicates 1547.

As can be seen, different historians highlight different statutes. Dunlop and Denman’s 1912 account provided the basic template for a century. Yet they overlooked 1572, to which it seems Kussmaul (1981) was the first to draw attention. In an important local study, Sharpe (1991) chose to begin with 1563, and confusingly cited 1576/7, which was only a continuation of 1572. In a footnote, Hindle (2004) stressed the origins lay in 1536 not 1563. Both Sharpe and Hindle ignored 1547, whereas Beier (2008) and McIntosh (2011) emphasise its significance and continuity with 1572.

Most strangely, the 1550 Act has been almost entirely neglected in studies of pauper apprenticeship, although its content has been observed in general histories of the poor law.[iii] Rose (1989) is unusual in citing the act in a footnote, but makes no comment. Further, there has been a lack of precision about the lifetime of these statutes and how they related to each other.

The result is that the current literature is extremely uncertain about what powers for binding children were on the statute books at different points during the sixteenth century.

A Revised Timeline

Clarifying the legislative genealogy matters for our understanding of a host of issues, including the shifting aims and ideology of state actors, the periodisation of pauper apprenticeship, the relative novelty of 1598, and the links between different statutes.

Based on my readings of the statutes, here is a revised statutory timeline:

- 1536 [lapsed]: Forced service or apprenticeship for beggars’ or vagrant children introduced – but act lapsed soon after (disagreement on exactly when).

- 1547 [repealed]: Revives similar law as 1536, with punishment of enslavement, but repealed in 1550.

- 1550: Replaces 1547 with almost identical clause, without enslavement and a few revisions (e.g. terminates at lower age limit).

- 1563: Compulsory apprenticeships in husbandry introduced, alongside forms of compulsory service for age 12 and over, creating overlapping power with 1550 provision.

- 1572: Replaces 1550, with revisions.

- 1598: Replaces 1572, with revisions.

Hence the basic policy of binding poor children to long-term service was introduced briefly in 1536, then revived in 1547, after which it remained in some form up to and through 1598 – alongside a complementary power from 1563 that could bind some of the same children (age categories overlapped 10-14) to similar long-term apprenticeship.

This is a complex history. For now I only wish to make the key point that the story of pauper apprenticeships properly begins with 1547 and 1550, passed by the same Parliament, with the latter as the foundational statute. Rather than emerging in 1536 only to lay dormant until 1572, there is a continuous half-century legal tradition prior to 1598. The fact that this originates in the ‘Slavery Act’ of 1547 (which I am obliged to call notorious) for punishing vagrants has implications for how we understand the place of pauper apprenticeships in the development of social policy.

The inattention to 1550 is even more remarkable when we look at the act as a whole. Its main purpose was to repeal 1547 and restore an earlier poor law of 1531. However, since 1531 had no provision on binding poor children, a significant section of 1550 was dedicated to retaining the 1547 clause on beggars’ children with revisions and elaborations. The binding of poor children is the subject of four clauses (X to XIII), which together constitute over one-third of the entire statute (by number of words). It was therefore not merely an incidental and easily-overlooked feature, but central to the 1550 Act.

[i] All references to statutes from Statutes of the Realm accessed via HeinOnline.

[ii] A non-exhaustive lists of brief surveys or citations of statutes: J. Dunlop and R.D. Denman, English apprenticeship and child labour: a history (1912), p.248-9; Ann Kussmaul, Servants in Husbandry in Early Modern England (1981), ‘Appendix’, p.166; Mary B. Rose, ‘Social Policy and Business; Parish Apprenticeship and the Early Factory System 1750–1834’, Business History, 31:4 (1989), p.6; Deborah Simonton, ‘Apprenticeship: Training and gender in eighteenth-century England’ in Maxine Berg (ed.), Markets and manufacture in early industrial Europe (1991), p.229; Pamela Sharpe, ‘Poor children as apprentices in Colyton, 1598-1830’, Continuity and Change, 6:2 (1991), p.253; Steve Hindle, On the Parish?: The Micro-Politics of Poor Relief in Rural England c.1550-1750 (2004), p.196; Joan Lane, Apprenticeship in England, 1600-1914 (1996), p.3; A.L. Beier, ‘“A new serfdom”: labour laws, vagrancy statutes, and labor discipline in England, 1350-1800’ in A.L. Beier and Paul Ocobock (eds), Cast Out: Vagrancy and Homelessness in Global and Historical Perspective (2008), p.46-47; Marjorie Keniston McIntosh, Poor Relief in England, 1350–1600 (Cambridge, 2011), p.123, 136, 229.

[iii] Noted in Paul Slack, Poverty and policy in Tudor and Stuart England (1988), p.122.