Taylor Aucoin

On the night of 8 April 1693, a burglar broke into Thomas Masterman’s house in Stokesley, making off with the hefty sum of £2 10s. To identify the thief and reclaim his money, Masterman trekked south through the north Yorkshire moors to Byland Abbey. There he met with William Bowes, described by Masterman as ‘a man who pretends to discover stolen goods by casting of figures or otherwise’. Bowes proceeded to do just that, and ‘in a glass did show…the likeness & physiognomy of Richard Lyth’, a tailor to whom Masterman had recently repaid a small debt. Bowes advised to look no further than Lyth for the thief, adding that, ‘he could not have power to dispose of the money, but within a few days it would be brought again & thrown in a corner near [Masterman’s] house’. For this information and service, Bowes received one shilling in payment.[1]

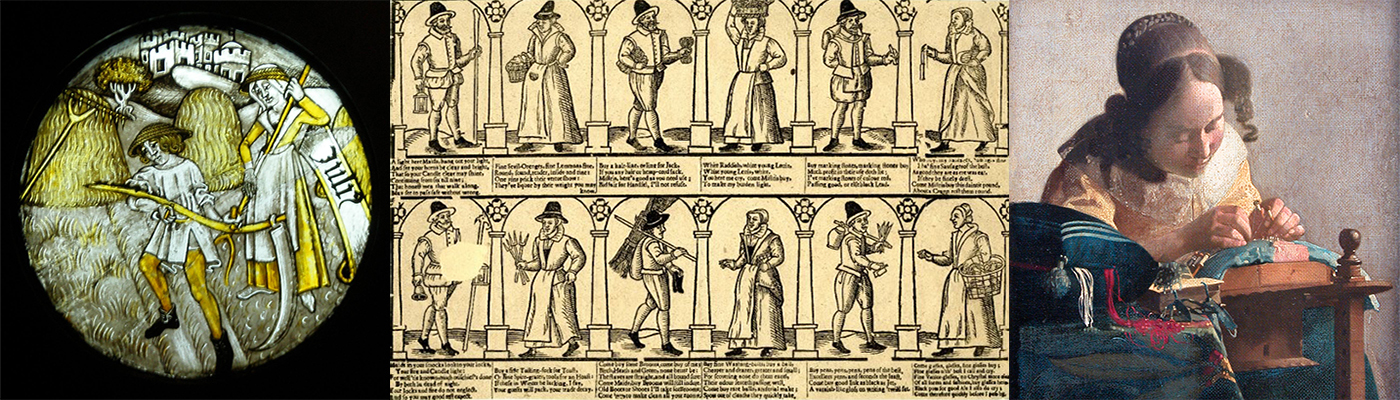

Masterman’s story, captured in a court deposition from the North Riding of Yorkshire, is not altogether unusual for the time. We know that many premodern English men and women similarly consulted and contracted local magical practitioners (variously called wisemen, cunning folk, or soothsayers) to cure ailments, find lost or stolen property, or fix other problems. While reading through court depositions from quarter sessions of the peace for counties of northern England, I’ve come across a number of references to such ‘practical magic’, as well as more classic examples of malicious witchcraft. And since it’s Hallowtide, it seems the perfect time to survey these magical findings and discuss their relevance to the project: what they suggest about the relationship between work and magic during this period, and the ways in which some magical activities could constitute ‘forms of labour’ in their own right.[2]

In the northern quarter sessions at least, I’ve found that depositional evidence of magic usually derives from just a few types of criminal cases.

Most obvious are those of witchcraft, where the very crime concerned was the use of black magic to harm people or property.

While witchcraft was legally a felony and should have been tried at higher courts like the Assizes, cases could initially be examined at the county quarter sessions.[3] And so we sometimes get depositions like those against widow Dorothy Bentum of Coppull, Lancashire, who in 1676 allegedly ‘did harm by her tongue’, bewitching one women into madness and another to death.[4]

Evidence of magic also crops up in defamation cases, when plaintiffs brought suits against those who slanderously accused them of witchcraft and thereby harmed their public reputation.

Like witchcraft, defamation was usually handled by other courts in England, namely those of the church.[5] Nonetheless, similar cases could be brought up at the quarter sessions, like when Anne Harrison, a widow of Burland, Cheshire deposed in 1662 that her daughter-in-law had uttered the following defamatory words against her: ‘God blesse me against all witches and wizards and thou art one’.[6]

In such cases of defamation or witchcraft, magic was either integral to the crime or the crime itself. Yet magic could also be more incidental or tangential to a case. Accusations of witchcraft, for example, sometimes prompted retaliatory breaches of the peace. In a 1690 physical assault case from Idle, Yorkshire, Martha Thornton attacked James Booth and ‘dasht his head against a cupboard’ because the latter man claimed Martha had ‘destroyed’ his daughter ‘by witchcraft’ and also ‘did ride on witching every night’.[7]

But as Thomas Masterman’s story implies, not all depositional references to magic were negative. Theft cases – the vast majority of business handled by the quarter sessions – sometimes yield references to practical, helpful magic, as plaintiffs sought to track down their missing goods. In a case that I’ve already covered in detail for a previous blog post, Henry Lucas of Hoghton, Lancashire travelled across the county border in 1626 to consult with a ‘wiseman or witch’ in Yorkshire about his mother’s stolen cow. The wiseman provided a vision ‘of those persons that took the said heifer’ and told his clients where the cow might be found.

Similarly, in 1612, when a servant-boy named Thomas Aston went missing in Over, Cheshire, his master and mistress went to ‘blynd Burnie, to know whether he were quicke or dead’. Blind Burnie obliged, and ‘told them he [Aston] was alyve and lustie and was in Torpley parish and that at Michaelmas he would come home again to fetch his cloathes and the rest of his hire’.[8] Blind Burnie’s foresight proved myopically off target – not altogether shocking considering the wizard’s name!

It is these references to soothsaying and consultation that most clearly qualify as ‘magical work activities’ for the purposes of our project. They were transactional in nature, and although technically illegal, the magical acts themselves weren’t usually under criminal investigation. While rare, they hint at a much wider service industry of magic – what we might call a ‘magiconomy’. Like much else in early modern society, it was underpinned by reputation. As Alan MacFarlane demonstrated in his classic study of witchcraft in early modern Essex, people would travel long distances to consult specific cunning folk because of their famed skill, and not necessarily those practitioners nearest to them.[9] The same seems to have been the case in the north: Thomas Masterman and Henry Lucas each travelled over twenty miles to remote locations for their respective magical consultations.

Cunning folk also had a complex relationship with remuneration. Although many were poor characters living on the periphery of society, some refused payment for their services, claiming that compensation disrupted their abilities.[10] Interestingly, this represents something of an antithesis to work by commission or piece-rate, challenging the assumption that the quantity/quality of labour or service necessarily increased with the incentives offered. It also reinforces an argument that our project champions: that unpaid work was still work.

All that being said, many practitioners of ‘good’ magic did indeed charge for their services. William Bowes of Byland Abbey certainly received one shilling for his prognostication. We don’t know if Blind Burnie or the Wiseman from Yorkshire also had going rates, but one large and complex case, from our sample of quarter sessions depositions in eastern England, suggests the potential complexity and variance of magical service transactions.

In 1590, the Hertfordshire quarter sessions heard a case against Thomas Harden of Ikelford, who was ‘rumoured to be a wiseman and skilful in many matters’. The depositions include a veritable laundry list of magical work activities and corresponding prices: 6d (with more promised) to cure a ‘changeling’ child who could neither speak nor walk; 5s worth of money, bacon and pigeons to find a stolen parcel of clothes; 12d (with 20s more promised) to discover two lost horses; 40s (with an extraordinary £20 more promised) to divine who had burned down a house.[11]

There was clearly a pattern of paying a smaller sum upfront, with more promised upon the (presumably) successful completion of service. It was this last criterion that seems to have landed Harden in hot water, essentially for fraud. The problem was not so much that he illegally practiced magic or witchcraft (the deponents gladly and openly consulted him) but that he provided faulty prognostications and cures and then refused to refund customers. Thomas Masterman may represent a similarly dissatisfied client, since his deposition at the beginning of this post was actually levelled against William Bowes and pointedly stated that Bowes merely pretended to discover lost goods.

In Thomas Harden’s case, he eventually confessed to the charges of fraud. He admitted ‘that he could do nothing’, but added that ‘there was a time when he could do much’, before a ‘nobleman of the realm’ tricked him out of his ‘familiar spirit’ and a ‘great many books’. Such cases of fraud imply, as many scholars have been at pains to point out, that practical magic was a craft like any other: it required skill, tools of the trade, and a reputation for effectiveness, with avenues in place for quality control.[12]

And just like many other early modern forms of labour, magic was gendered, with discovering lost property generally coded male, and charms, incantations, and curses usually coded female.[13] This division of labour, and the types of quarter sessions cases most likely to contain evidence of magic (i.e. witchcraft, theft, fraud), help explain the overrepresentation in our depositional references of men as positive practitioners and women as negative ones.

Much more could be said about these magical work activities. For example, as our research proceeds apace on samples of court depositions from northern and eastern England, there may be scope in the future for comparisons between regions or types of courts. But regardless, practical magic demonstrates the diverse forms which early modern labour could take, and the incredible richness of early modern depositional material for a wide range of research topics.

[1] North Yorkshire Record Office (NYRO): QSB/1693/230.

[2] The literature on magic and witchcraft in premodern England is obviously vast, but on popular or cunning magic in particular see Tom Johnson, ‘Soothsayers, Legal Culture, and the Politics of Truth in Late-Medieval England’, Cultural and Social History, (2020) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/14780038.2020.1812906; Catherine Rider, ‘Common Magic’, in The Cambridge History of Magic and Witchcraft in the West: From Antiquity to the Present, ed. David J. Collins (Cambridge, 2014), pp. 303–31; Owen Davies, Popular Magic: Cunning-folk in English History (London, 2008); Alan MacFarlane, Witchcraft in Tudor and Stuart England: A Regional and Comparative Study (Abingdon, 1970), ch. 8; Keith Thomas, Religion and the Decline of Magic: Studies in popular beliefs in sixteenth and seventeenth century England (London, 1971).

[3] On early modern legal jurisdiction over magic and witchcraft see MacFarlane, ch. 3.

[4] Lancashire Archives (LA): QSB/1/1676/ Information of Richard Fisher, Examination of William Millner.

[5] For some examples from the Diocesan Courts of the Archbishop of York: https://www.dhi.ac.uk/causepapers/results.jsp?keyword=witchcraft&limit=50

[6] Cheshire Archives and Local Services (CALS): QJF/90/1/100.

[7] West Yorkshire Archives Service (WYAS): QS1/29/9/ Examinations of John Thornton, James Booth, Lawrence Slater.

[8] CALS: QJF/41/4/71-73.

[9] MacFarlane, pp. 120-1.

[10] Johnson, p. 6; Rider, p. 321; MacFarlane, pp. 126-7.

[11] Hertfordshire Archives and Local Studies: HAT/SR/2/100.

[12] Johnson, p. 10; Thomas, pp. 212-52; Davies, ch. 4.

[13] On the gender of magical practitioners, see Johnson, p. 5; Davies, ch. 3; MacFarlane, pp.127-8. And for cutting-edge work on the gender dynamics of practical magic, as a craft and service industry in premodern England, see the research of Tabitha Stanmore, University of Bristol.