GABRIELE MARCON

Early modern mines ranked among the most populated workplaces of the preindustrial world. Both men and women engaged in mining activities. Yet women’s work is either scarcely documented or irremediably lost.

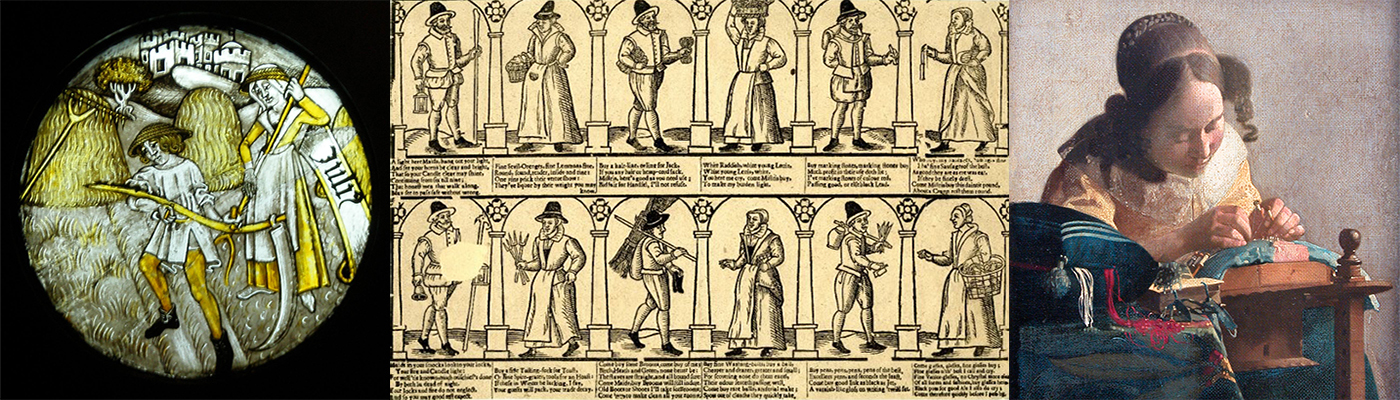

Women worked in various sectors of the preindustrial European economy. In recent decades, historians have resurfaced women’s lost labour by adopting innovative methodologies that blur clear-cut distinctions between ‘productive’ and ‘unproductive’ work.

This renewed interest have led to discovering women’s contributions to the economy in the household, in craft guilds, in agricultural fields, and in princely courts. Historians are yet to make similar headway in correcting for the relative absence of women in the records of early modern European mines. New research on German miners in Renaissance Italy offers ways to recover some of women’s lost labour.

A women-less industry?

The history of mining has been chiefly narrated through the lens of economic history and the history of technology. These approaches focused primarily on mid-aged, wage-earning male miners as workers of the coal mining industry in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century. But the equivalence between men and labour in the mines has a longer history.

Ancient and early modern theories on the origins of metals represented Nature as a nurturing Mother who created metals in the womb of the Earth. Ancient compilers such as Pliny (23-79 CE) understood this generative function as a way to conceal metals from men’s avarice. However, in sixteenth-century Europe the expanding economy of mineral resources called for a general reinterpretation. Nature was no longer inaccessible, and it could be ‘altered and manipulated by machine technologies’ for the sake of human well-being.[1] The protagonist of this transformation became those courageous men who, by dominating Nature, descended into the Earth’s womb, and returned with the material means for human economic development.

This utilitarian and mechanic attitude towards the extraction of mineral resources gave rise to gender stereotypes and tropes of masculinity in early modern Europe. Mining labour was thus supposed to have been classified as unfit activity for women, who did not possess the necessary strength to exert dominion over Nature and could not carry out physically demanding activities.

German women in Renaissance Italy

Did this normative view completely apply to early modern mines? Over the past few years, I have studied mining activities in Renaissance Italy as part of my larger interest in the migration of German miners across the early modern world. Despite their low production output, sixteenth-century mines in the Grand Duchy of Florence and the Republic of Venice maintained rich documentation on women’s participation in this industry.

In Italy, German women arrived with their husbands from Erzgebirge (the Ore Mountains), Tyrol, and Carinthia. As part of the family labour unit, they worked in wage-earning activities that challenged gender stereotypes. One notable example is Barbara Freisesser. Barbara worked every week (six-days a week) from 1559 to 1560 in front of an iron furnace, actioning the air-pumped bellows of her husband’s smelting workshop. The temperatures Barbara was exposed to were so high that a few years earlier a male Medici official refused to work under the same conditions – he could not take the heat!

In December 1546, Cristina Ule arrived from Sankt Joachimsthal with her husband and worked in the Medici mines until 1553. As early as 1547, she was appointed to supervise miners’ working shifts. Because a bell that would strike at the start and at the end of a miner’s shift was installed only later, Cristina was tasked to time each miner’s shifts by ‘counting the hours’ off the clock located at the pit’s entrance. Her time keeping was then passed on to the Medici official who paid the miners every Saturday.

German women also headed money lending institutions responsible for the distribution of wealth in the mining community.[2] If you were a miner in the sixteenth-century Medici enterprise and needed a loan, you would have most likely asked for it from a woman.

Gender inequalities and coercion

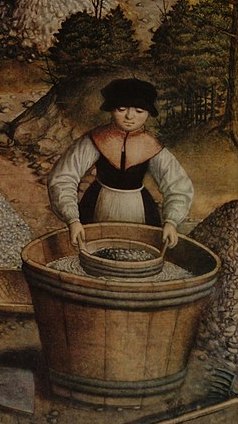

Even though women performed various tasks, a gendered-based division of labour and pay-gap characterized their working experiences. Newly reopened mines offered employment opportunities to local workers. Women from nearby villages worked for the mines as unskilled labourers in hauling and carpentering activities. Because these were tasks performed for the mines and not in the mines, local women were not considered fully-fledged members of the mining community – a fact that prevented them from benefitting from legal rights and better social positions.

Women were also paid less than men. When employers tasked male workers with unskilled activities, men received higher wages than women. Male workers often carried out these activities alone, and received daily salaries that ranged from eight to twelve soldi. By contrast, women performed labour in crews that comprised up to nine co-workers, and received wages for tasks that were completed in longer periods of time.

Co-operative work and payments calculated for long employment periods lowered women’s average remuneration. Serena, a local woman from Retignano (Versilia, Tuscany) worked as an unskilled labourer for 127 days between 1559 and 1560 in the Medici silver mines of Pietrasanta. She often performed carpentering and hauling activities together with other women, and received wages for tasks that occupied her for as long as 23 days. In these cases, Serena’s daily wage was still only calculated at around two to four soldi.

Employers often used women to cut labour cost. In 1559, an official of the Medici mines employed six men as miners and 20 women to quarry the earth residuals from the mines. The latter had to be paid half ‘in order to spend less’. Women’s work was cheap and was part of a coercive mechanism that mining officials often established to supply unskilled labour force to the mines. Because the low-skilled tasks were a significant part of labour activities in the mines, local workers were not allowed to leave their villages and were bounded to perform this labour ‘anytime they were asked to’.

Women’s lost labour

Women were not absent from mines; their lost labour only awaits to be recovered. A more systematic analysis of women’s work in the mines would shed new light on the relationship between freedom and work in early modern Europe. Furthermore, it would challenge tropes of masculinity in extractive industries around the world, and provide new historical understanding of women’s participation in the current mining rush for low-impact natural resources.

Dr Gabriele Marcon is a Lecturer in European History (1450-1750) at Durham University, UK. His research lies at the intersection of labour history and the history of science, and focuses on the extraction of natural resources in Renaissance Italy. He has recently received his PhD in History from the European University Institute (Florence, Italy) with a thesis titled “The Movements of Mining: German Miners in Renaissance Italy (1450-1560)”. He is the co-convenor of the European Labour History Network working group “Labour in Mining”.

[1] Carolyn Merchant, The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology, and the Scientific Revolution, (New York: HarperOne, 1980), 68.

[2] For a more exhaustive analysis of these activities, see Dana Velasco Murillo, ‘Laboring Above Ground: Indigenous Women in New Spain’s Silver Mining District, Zacatecas, Mexico, 1620–1770’, Hispanic American Historical Review 93, no. 1 (1 February 2013): 3–32.