CAROLINA UPPENBERG & MARTIN ANDERSSON

Complaints about the lack of suitable servants are one of the historical continuities of the labour market – the lament of landlords and housewives, farmers and state officials echoed through the centuries. Nowhere and never did the supply of people willing to take up work in the household of someone else seem to be enough. This may look strange or counterintuitive: in a poor society, where people lived only one cold summer away from the brink of starvation, where vagrancy was a crime and where the household was a necessary institution both legally and for survival, resource pooling and to organize work in order to live, the servant position offered obvious advantages. A servant lived in the household of her/his master, food and lodging was part of the wage, and the contracts were long – servants were mostly protected from the dangers of the slack periods during winter since they were employed for the year. Still, the position of the servant had to be enforced by state authorities, fenced about by strict regulations, and praised in didactic writing. In our conference contribution, we offer one explanation for this, i.e., that precisely this specific – and seemingly attractive – form of remuneration that shaped the servant position had a coercive logic.

The fundaments of the Swedish servant legislation were legally inscribed already in the earliest thirteenth-century manuscripts, during a time when the unfree thralldom institution had not yet been abandoned. The basic idea of the servant institution was that all people should belong to a landed household; if not as part of the landowning family, then as a servant, a crofter, or through some other kind of labour arrangement. Needless to say, the servant position was a position for the poor. In the mediaeval regulations, it was stated that anyone who owned less than a certain threshold had to become a servant. During the 17th century, when the Swedish Crown increased its need for soldiers, this regulation was extended even further, so that now all people had to get themselves laga försvar, ‘legal protection’. This could be reached either through considerable wealth, or else, and most commonly, through being properly landed. Landless people, on the other hand, had to seek themselves a position as servant, although in practice at this time it had primarily become the solution for unmarried men and women. The alternative was either to become a soldier, or to be subject to vagrancy laws and related punishment. However, even for servants who took up the position without being forced, the coercive measures were part of the logic of the institution.

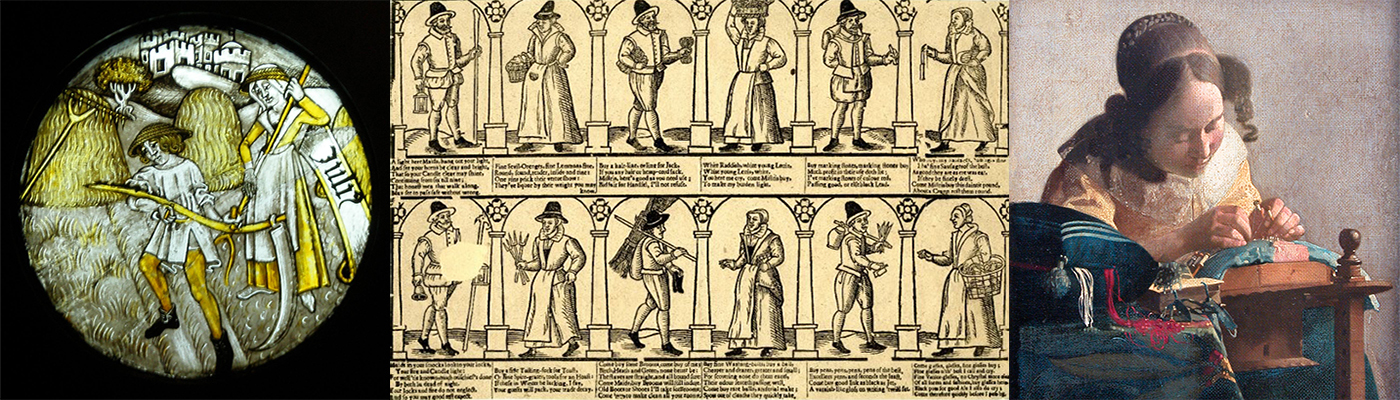

Servants were, in the early 13th century as well as during the latter part of the 19th century, remunerated through a specific tripartite system: the fastening penny, the board and lodging, and the cash wage. The fastening penny was a small sum, or an object handed over to the servant-to-be as the contract was sealed. However, the fastening penny could only be accepted when the servant had resigned from his or her former master – thus, the servant was deprived of the possibility of making use of a potential bargaining position. Once the fastening penny had been accepted, the servant was now bound to the master for the next full year, and subject to the risk of being brought back through force or being dragged to court if he or she tried to run away earlier.

Board and lodging may seem like the ultimate way to be remunerated in a subsistence economy, but in fact, this too fulfilled the function to reproduce the servant position. Not only were servants deprived of using these resources as they wished; but the fact that the servant had to live, eat, sleep, and keep all his/her belongings in the house of the master made it almost impossible to escape. Since only a tiny fraction of the wage was paid in cash or in anything that could be accumulated as savings for the future, by the end of the working year, the servant was as poor as he or she had been in the beginning. The servant had survived, but as the major divide between people was between landed and non-landed, the hard working year had not taken the servant any further towards the landed position, since the lion’s share of the wage had been consumed during the year. Moreover, a better meal could be used as a reward, as could a worse be as a punishment – the control over the remuneration remained in the hands of the master, a potential tool for making servants work faster, harder, better.

The cash wage, finally, carried its own coercive features. The most obvious was that all cash wages were to be paid only at the end of the working year. Any disagreements, premature evictions, or a servant’s absconding meant that no cash wage was paid. Moreover, servant wages were legally restricted by proclamations of maximum levels, thus preventing bargaining and the possibility to earn more. On top of this, were masters forbidden to remunerate servants with any forms that would potentially make them more independent, such as share-cropping arrangements or through giving over a part of the harvest.

While most servants did not need to be forced physically to take up the servants position (either because it was just what young, landless people did, or else because the threat of punishment, and even coerced recruitment into the army, would be enough to choose service) the forms of remuneration peculiar to the servant institution, when studied in detail and through the lens of coercion, may, perhaps more clearly than long timeseries of servant real wages, give an answer to why we find a 500-year long lament about the lack of servants.

Martin Andersson is a researcher at the Division of Agrarian History at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences in Uppsala, Sweden, and a visiting scholar at the Cambridge Group for the History of Population and Social Structure at the University of Cambridge, UK. His research deals with economic, demographic and social aspects regarding servants and other groups of rural working poor in medieval and early modern Sweden.

Carolina Uppenberg holds a PhD in Economic History and is researcher and PI for the project “Challenging the domestic. Gender division of labour and economic change studied through 19th century crofters’ households”, a three-year project funded by the Swedish Research Council, at Stockholm University. Recent publications include the published PhD thesis Servants and masters (Gothenburg: 2018), “Masters writing the rules: how peasant farmer MPs in the Swedish Estate Diet understood servants’ labour and the labour laws, 1823–1863”, Agricultural History Review 2020 (68:2) and a chapter in Servants in rural Europe 1400-1900, ed. Jane Whittle, Woodbridge: 2017.