HANNAH ROBB

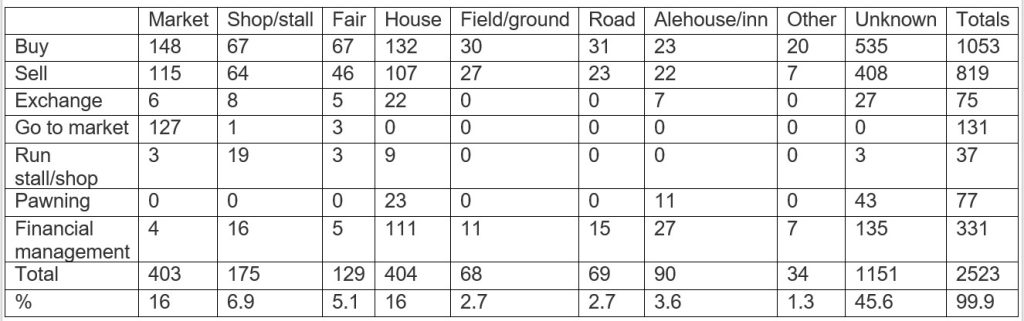

This research comes from the ‘Forms of Labour’ project at the University of Exeter and reflects on the work activities associated with buying, selling and lending in early modern England. Throughout the project we have been recording work activities and because of this we capture in our database the work of both buyers and sellers. This presents a different perspective to traditional economic models that focus on transactions and instead we can identify individuals buying and selling and performing all the intermediary activities associated with trade including mediating prices, valuing livestock, weighing and measuring goods, standing as surety and travelling to and from the market. Within the category of commerce, and including two additional subcategories of pawning and financial management, I have overlaid a series of spatial descriptors to our work activities seen in the table below. The categories reflect the spaces described by the actors in our depositions but also the division of commerce between open regulated trade in marketspaces and private commerce behind closed doors in the home. This is never perfect; trade was ‘a disorderly amalgam of commercial energy, custom and opportunism, in a continuous process of evolution’ and the private space of the home was still governed by the regulations of open trade in the market.[1]

In this short blog here I want to explore the trade in what Richard Britnell has termed ‘intermediate zones’, those spaces that blurred the boundaries between domestic living, manufacturing and commerce.[2] Robert Wolley’s shop, described in the depositions of a defamation case in St Albans in 1595, is a perfect example of the shop as a multifunctional space. Agnes Hope came to the shop to buy cambric from Wolley but being a seamstress stayed to work on some sewing to take advantage of the warmth thrown out by a pan of coals that had been warmed for Robert Wolley’s wife who had just delivered a baby, ‘because [she] the mother was then very cold’. Agnes Hope was not the only one to take advantage of the warmth. Gathered in the shop were James William and Hugo Summer, both of whom described themselves as being a familial relation to Robert Wolley, and William Towe all of whom stood or sat around the coals with the new mother and baby. From the shop this small congregation were privy to defamatory words bawled out in the street. There is no sense of the shop or stall being a private space despite the intimate activities going on inside. Wolley’s shop provided a practical function of warmth that rendered it useful for multiple purposes and in doing so it drew in a range of work and social activities. The commercial space of the shop here is seemingly being negotiated and is at once a private space of domestic living and a public one of commerce.[3] In the table below we can see how much trade by-passed formal marketing structures and instead was conducted in the home, at a shop, stall or in an alehouse or inn.

In the table above commercial work in shops, stalls, alehouses and inns accounts for 10.5% of the recorded work activities. Dividing the actors into buyers and sellers in the chart below we can see that within these intermediate zones, women make up a large proportion of sellers. Evidence from the depositions suggests that women took an active role selling produce at stalls particularly when working alongside their husband or in their husband’s trade. When John Dawlyn approached the stall of the butcher Lodovicus Spratly in Southwark to settle a debt, Lodovicus only left his stall when his wife, Fortuna, came to take over and run the stall selling meat.[4] Husband and wife Thomas and Mary Mannings were in their grocer’s shop in Norwich where Mary was overseeing her servant, William Benn, stripping tobacco whilst her husband served customers.[5] When Agnes Moore married her husband, she visited her neighbour to extend friendship stating ‘I hope I shall be your neighbour standing in my shop selling meat as your wife doth in hers selling bread’.[6]

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the intermediate zones that blurred the distinction between domestic living, manufacturing and commerce offered women a space in which they could sell goods. Significantly the majority of the women recorded in our database working in shops were married women, those most likely to command a household and be able to engage in retail in their own home. When we think then about Jon Stobart’s call to identify agency in the shopkeepers and grocers of the retail revolution in the eighteenth century, we should also be thinking about women as sellers and their role in the earlier shops and stalls of the sixteenth and seventeenth century. [7]

Hannah Robb is a post doctoral research associate at the University of Exeter working on the project, Forms of Labour. Her research explores small scale credit and financial management in the early modern period. Her work uses instances of debt litigation and considers the relationship between litigation, legal codes and contracts of credit for concepts such as trust, faith and truth in economic relationships.

[1] Beverly Lemire, ‘Plebeian commercial circuits and everyday material exchange in England, c.1600-1900’, Buyers and Sellers: Retail Circuits and Practices in Medieval and Early Modern Europe, ed. Bruno Blonde, (London, 2006), pp. 245-266, p. 245.

[2] Richard Britnell, ‘Markets, shops, inns, taverns and private houses in medieval English trade’, Buyers and Sellers, pp. 109-123.

[3] Hertfordshire, ASA8/8/5, Alexander Done v William Towe, 1595-1612.

[4] Hertfordshire Record Office, ASA8/8/26-28.

[5] Borthwick Institute of York, DN/DEP/53/58A.

[6] Hampshire Record Office, 21M65-C3-10, 1590-1596.

[7] Jon Stobart, Sugar and Spice: Grocers and Groceries in Provincial England, 1650-1830, (Oxford, 2013).