AMY FROIDE

After seven years together, the marriage of Sarah and John Mould was in trouble. It wasn’t just the marriage that was suffering though, it was also the household business and grocery trade. It was 1704 and Sarah had come before London’s Consistory Court to ask for a separation from bed and board.[1] Sarah Bishop had been a widow with children and a shop when she married the apprentice John Mould and he became her second husband. Sarah mentions debts left over from her first marriage and how she and John constantly fought over their business and the shop. She explicitly says that her husband was not good at business. Perhaps not surprisingly, John Mould presented a very different story to the court. John implied that his wife did not have much of a business or household when he married her and that she was more in debt than she was worth. He acknowledged that he had only been an apprentice, but implied that he tried to improve the trade and the shop. The children from Sarah’s previous marriage were also a point of contention in this second one. Sarah said John would not pay for the children’s schooling and she had to take money from the till to do so on the sly. John also refused to apprentice his stepchildren. The Moulds were a blended family which created its own issues that led to this separation case. Sarah’s previous marriage meant that she came to her second with some sense of entitlement and experience in trade. She felt that she knew how to run a business, and not only did Sarah not defer to her second husband in business matters, she also contradicted him. John complained about the household’s debts and the decay of their business, both of which he blamed on his wife. He also accused her of taking money and goods and not recording them in their accounts. Could this marriage and this household trade be saved?

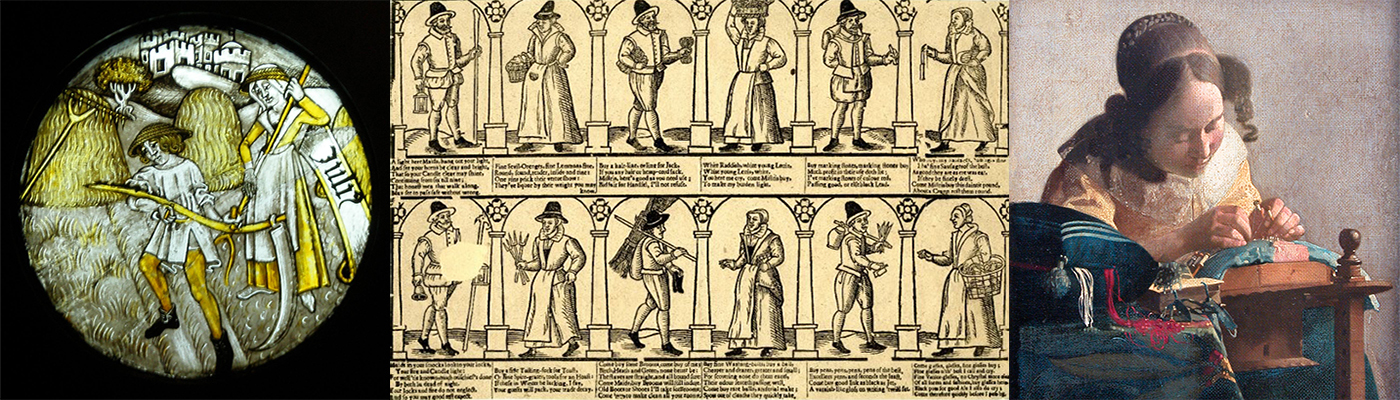

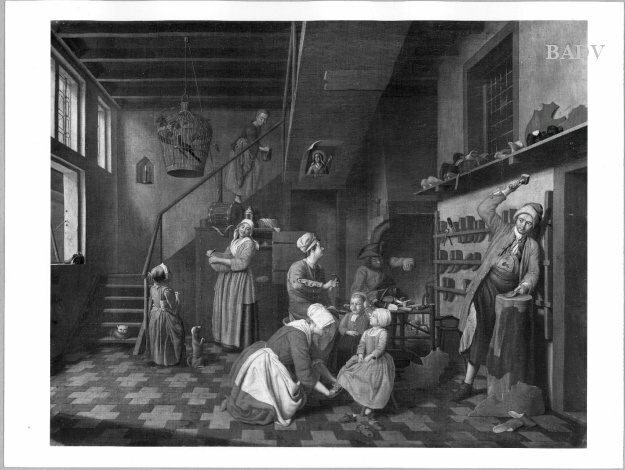

When a couple in early modern England chose to separate it had serious ramifications for them, their children, and even extended kin like parents and siblings. Marital separation also had an impact on family workshops, trades, and businesses. The economic side of marital separation is my current research project. There were two primary legal strategies for obtaining a legal separation: adultery, cruelty, or a combination of the two. Historians have focused on the details of adultery and cruelty because sex and violence are guaranteed topics of interest, but there has been much less interest in the economic issues that were also prominent in the separation cases. While adultery or violence may have been the reason a wife or husband gave for a separation request, what the two spouses ended up talking about in their testimonies was money. There were disputes over dowries, household trades and businesses, and the maintenance and training of family members post separation. Using witness testimony from marital cases before London’s Consistory Court in the early decades of the 1700s, I examine the economic aspects of separation. This court was frequented by London’s middling women— female traders, artificers, and businesswomen. Because of their social status and occupations, when these women pursued a separation, issues involving the family business or trade rose to the fore. Wives and husbands provided she said/he said testimonies complaining of debts, business mismanagement, stealing from the business, removing trade stock from the household, and not being a good partner (in business as much as marriage). A subset of cases between widows and their second (or third) husbands illustrates the friction that occurred between a woman already familiar or working in a business or trade and a husband who might expect to be in charge. The separation cases between remarried spouses are a significant source of evidence for the work performed by wives in early modern London. The cases reveal that wives were key partners in the family workshop or trade, but they also remind us not to assume that such partnerships were always positive or successful for the marital couple.

Amy M. Froide is Professor and Chair of the History Department at UMBC (University of Maryland, Baltimore County). She teaches courses in early modern British and European Women’s History. She is the author of Silent Partners: Women as Public Investors during Britain’s Financial Revolution, 1690-1750 (Oxford University Press, 2016). Her other books include Never Married: Singlewomen in Early Modern England (Oxford University Press, 2005) and Singlewomen in the European Past, 1250-1800 (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999), co-edited with Judith M.Bennett. Professor Froide has served as the book review editor for the Journal of British Studies and the Director of UMBC’s Entrepreneurship & Innovation Minor. She is currently working on the Charitable Corporation scandal of 1732 and the economic side of marital separation.

[1] London Metropolitan Archives, London Consistory Court, DL/C/199 Personal Answer Books, folios 30, 47, John v Sarah Mould, 1704.