TIM REINKE-WILLIAMS

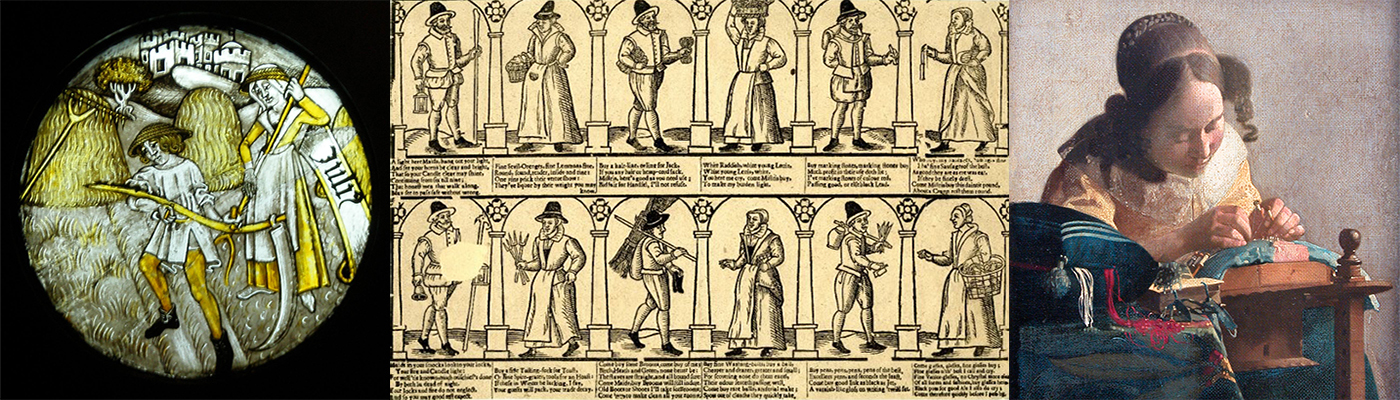

How many women sold alcohol in early modern England, and did this vary over time and by region? These seem like questions that social and economic historians ought to have no problem answering, but at present no one has gathered the data to come up with any firm conclusions. Projects on women’s work at the University of Exeter and on intoxicants at the University of Sheffield have expanded knowledge of related topics significantly, but the former has explored the diversity of occupations by gender without looking at specific forms of labour in minute detail, while the latter has been preoccupied with who drank alcohol, rather than who produced and sold such products.

By contrast, medievalists such as Judith Bennett and Marjorie McIntosh were thinking about these matters in the 1990s and 2000s, arguing that by the sixteenth century alewives and brewsters were being marginalised from the profession (although they disagreed on the timing and extent of the process). Early modernists are familiar with these arguments, but have accepted them rather unquestioningly, so there is a need to gather fresh data and test the rigidity of these arguments.

An obvious set of records to turn to would be licenses granted by Justices of the Peace which enabled individuals to run public houses. Women do crop up in these records, but most often as widows who often got licenses to enable them to gain an income and stay off poor relief. Yet anecdotal material from church court depositions has revealed that it was common (although how common is unclear) for married women to run public houses on a day-to-day basis, despite their husbands having been granted the licences.

More research needs to be conducted on licenses, but they have clear weaknesses when it comes to analysing gender, so instead I used indictments from four of the Home Counties (Essex, Hertfordshire, Kent, Sussex) of those prosecuted for running unlicensed alehouses and similar establishments. When it comes to these records the historian may face the opposite problem of women being over-reported by neighbours or targeted unduly by the authorities, but the extent to which this was happening seems to have been minimal (especially if we compare the figures with those for ‘female’ crimes such as infanticide or witchcraft).

Using the assize calendars produced by J. S. Cockburn in the 1970s and 1980s I have located 222 individuals who were prosecuted for an offence related to an alehouse or victualling house, most often for operating without a licence. This is a small sample which I intend to expand geographically (by incorporating material from Middlesex and Surrey) and chronologically (taking the analysis up to at least 1642, and hopefully 1660), but I was able to present some tentative findings.

Firstly, there were discrepancies across the four counties. Indictments from Essex and Sussex made up almost three quarters of the sample, while only 15 people were indicted in Kent, none of whom were women. Such discrepancies might be explained by considering a combination of overall population size, the nature of the local economies, and in the case of Essex its reputation, all of which I intend to explore in more depth as I expand the dataset and deepen the analysis.

Secondly, in total about 14% of those indicted within the Home Counties were women (a figure which falls at the midway point between the 16% indicted in Essex and the 12% indicted in Sussex). This is a higher figure than a lot of data gathered by other historians of women’s work, where the figure for women working in the food and drink trades tends to hover around 8-10%, and as noted above (some) women may have been targeted unduly due to magisterial priorities or the micro-politics of the parish.

On the other hand, the indictments might provide a more accurate snapshot of how many women and men were running public houses on a regular basis in the first quarter of the seventeenth century. Male offenders were more likely to be accused of not only operating without a licence, but also of encouraging ‘disorder’, ‘drunkenness’ or ‘gaming’ on their premises, which suggests that the alehouses of ‘ill repute’ were more likely to be run by men than women, and thus that if anything the indictments underrepresent the number of women in the trade between 1595 and 1625.

As all of this suggests, the evidence is rich but open to different interpretations. Indictments clearly are not the only or best source to provide evidence about how the number of women running public houses changed over time and varied across space, but alongside licences and depositions they are another piece which might help historians complete the puzzle. As well as the problems inherent in comparing different kinds of evidence from different regions, there are also problems with how historians have sought to categorise descriptions of work.

When seeking for data produced by other early modernists on women in the drink trade, I often found that retailing of food was rolled in with that of drink. This is a sensible way to break down data, and I too collected material on victualling as well as alehouses, but are historians right to blur boundaries in this way? Contemporaries obviously saw all sorts of public houses (alehouses, inns, taverns, victualling houses, coffee-houses, even venues selling hot chocolate) as sites of potential disorder, but if we want to consider women’s freedom to trade across the centuries, perhaps we need to be more attentive to how changing consumer preferences and the creation of new types of venue impacted on their ability to run establishments from which alcohol was sold.

Tim Reinke-Williams is a Senior Lecturer at the University of Northampton and Fellow of the Royal Historical Society who researches the social, cultural and economic history of early modern Britain. His first book, Women, Work and Sociability in Early Modern London (Palgrave, 2014), discusses how metropolitan women cultivated positive reputations as honest individuals of good repute through fulfilling roles as mothers, housewives, domestic managers, retailers and neighbours. Tim has edited a volume of essays on shopping in the early modern period (forthcoming in 2022) and is completing a monograph on attitudes to men’s bodies in seventeenth-century England.