JOSÉ ANTOLÍN NIETO SÁNCHEZ

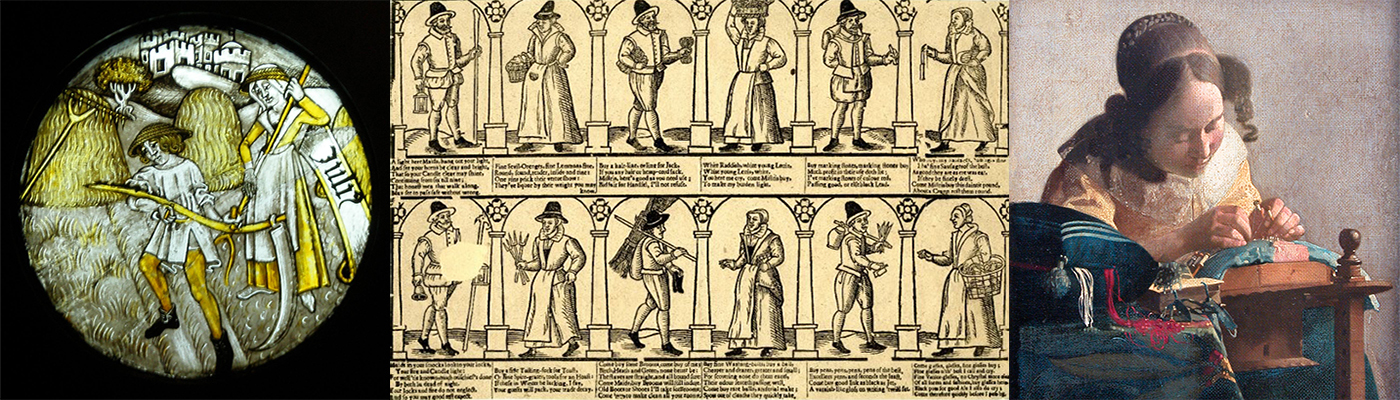

In Early Modern Europe, artisan work was reproduced through the apprenticeship system. In Castile, children around 14 to 16 years old joined apprenticeships as a training platform. Based on the data gathered from the indentures we can know how those apprenticeships were used as a survival strategy by some families in need, or how specific labour markets were formed at relatively early ages. Using data about the guardians we can learn about the reproduction of trades. Knowing when, where and in what trades children were placed as apprentices also tells us about the needs of rural and urban domestic units.

This article aims to establish a relation between the cities, as well as to establish if the work itself was able to create different urban networks throughout the Early Modern Age. Moreover, it attempts to combine the history of work with that of migration, urban history and social history. We analyse migratory flows and their relation with the behaviour of the cities and their labour markets, and the main features of the apprentices such as their age, their original background, their distribution within the workshops and the weight of the guilds in artisan production.

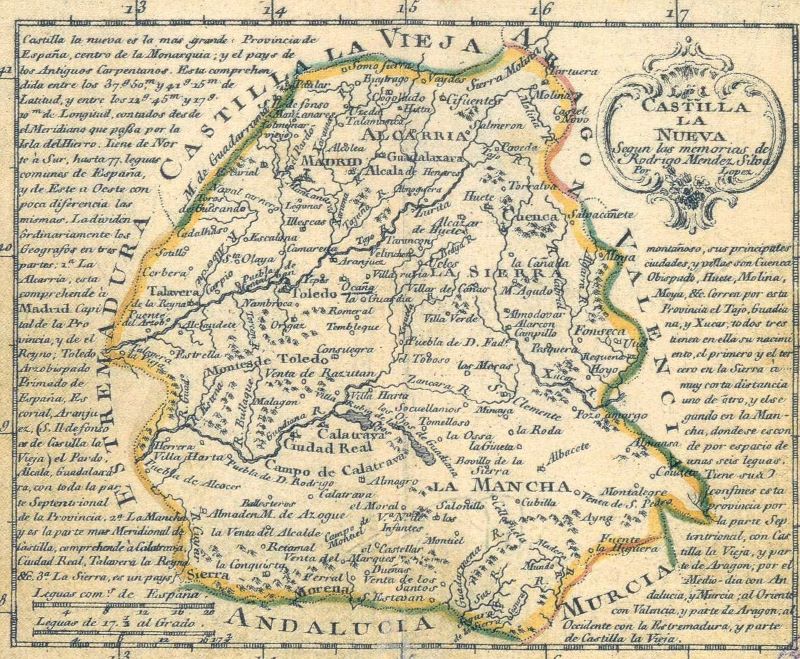

We have collected almost 8,500 artisan apprenticeship contracts signed between 1450 and 1800 from the twelve Castilian cities that had more than 10,000 inhabitants. We have selected samples of apprenticeships from three cities of Castilla la Vieja (Valladolid, Salamanca, Segovia), three from Castilla la Nueva (Madrid, Toledo, Cuenca), five from Andalucía (Sevilla, Córdoba, Jaen, Granada, Cádiz) and one from Murcia, and we have compared those with another 3,772 indentures from the Crown of Aragon extracted from the literature available. In total, there are about 12,000 contracts. Since these are early data on artisan apprenticeship during the Early Modern Age, there are inequalities in some of the series – especially in the seventeenth century. These have been resolved with the consultation of more archive data.

We can outline some preliminary conclusions. First, that until between 1600 and 1630, apprenticeship was a very open institution, capable of absorbing a good number of boys, and even girls and confessional minorities, though in fewer numbers. The obstacles to these groups came later which makes it difficult to speak of a rigid institution throughout its existence.

Second, the evolution of apprenticeship in the Spanish monarchy seems to go in conjunction with that of teaching or education in general. It transitioned from an early age of apprenticeship entry, which could hinder the attainment of basic general knowledge, to a later age of entry suggesting a prior period in school to gather knowledge in reading, writing and arithmetic. Perhaps we can say that the more knowledge the children had the better craftsmen they could become.

Finally, these apprentices featured in migratory flows that linked the countryside and the city, and ended up forming differentiated urban networks throughout the territory. There were cities that attracted boys from within the limits and its surroundings, but there were also those able to recruit child labour beyond the borders of the Hispanic Monarchy. The option of migrating had a lot to do with family needs, and above all, with the large number of orphans that existed in Castile. Apprenticeship is then revealed as a lifeline for many families without resources.

Much remains to be investigated, but studying apprenticeship makes it possible to establish some basic features of labour mobility, and explore the formation of urban labour networks which differed from those outlined in research on commercial exchange. Moreover, considering that there were times when the apprenticeship system integrated women and minorities, it would seem that artisan institutions were much more open than what has been traditionally perceived.

José Antolín Nieto Sánchez is a contracted professor in the Department of Modern History, of the Autonomous University of Madrid, where he coordinates the Social History Workshop group. He has published the book Artisans and merchants. A Social and Economic History of Madrid, 1450-1850, which was awarded the Villa de Madrid Prize in 2007 edition. Sánchez has been working on castillian guild issues for 30 years. He has opened a line of research on migration artisans and the transmission of technical knowledge (based mainly on apprenticeship contracts). He has written several articles on the subject in the Journal of Social History and in the volume directed by Maarten Prak and Patrick Wallis, Apprenticeship in Europe, published by Cambridge University Press in 2020. During 2017-2018 Sánchez has been principal investigator of a Latin American and Spanish Work Network, and is currently the second principal investigator of a project on Social History funded by the Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness (2019-2023).